It's interesting how few people have even considered waiting until adulthood before exposing children to religion, if at all. It seems a given in all religious traditions that you start children young, usually with a formal, staged, ritualistic program that is part memorization and recitation, part rite of passage. I think a strong case can be made against this parental impulse to continue what in most cases is an education parents themselves resented as children whose teachings they mostly abandoned as adults. The most common justification of childhood religious indoctrination goes something like this: "Well, I know that most of what is in the Bible is contradictory and of course I don't believe it literally, but I want my children to have a sense of tradition and community and belonging. I don't believe everything I was taught as a kid - I don't believe most of it really - but it's for adults to work out what they want to believe or reject - I think kids should hear it all, learn it, then if they choose to as adults they can decide whether to continue going to church or not."

Of course, just as compelling a case can be made for the opposite, that is allowing children to enjoy their childhood blissfully unaware that some adults are still fighting wars - cultural and literal - over the metaphysical interpretation of events that happened thousands of years ago in places most have never visited. We don't expose them to graphical sexual images as children but most of us are confident that when they are ready, they will be introduced to sexuality. Why do we have so much less faith when it comes to religion?

I think part of the answer lies in the fact that most of us have never seriously considered the question. The idea of a dogma-free childhood, one based on the simplest of ethical systems based on self respect and some variation of the Golden Rule, seems alien to those who have not experienced it, even dangerous. Suppose religion is like language - if you don't learn it at a young age you either never will or will always struggle with it?

Suppose indeed. I think this is the main fear of most religious traditions and why there is such a sense of urgency about getting kids enrolled in their Sunday schools and Bible camps and doing it early. Religious institutions whose livelihood depends on marketing to the next generation know that churches and temple would probably empty if only consenting adults, their minds unbiased and free to choose any religion or none at all, were to be first exposed to the central claims of these belief systems.

Imagine approaching the idea of choosing a religion as an educated adult. Even if you narrowed the possibilities down to some variation of Christianity, you are far from done.

Becoming a Christian is a bit like ordering a coffee at Starbucks: you have a perplexing menu of choices. First, you have to choose which side of the arguments of the Council of Ephesus in 431 you most agree with (to determine if you want to join the Assyrian Church). Then you should review the Council of Chalcedon in 451 to determine if you want to join the Oriental Orthodox. Most Christians are not affiliated with those two, so if you believe there is safety in numbers, you then come to the next big divide East or West, Orthodox or Roman Catholic. Each excommunicated the other, so you better choose correctly. If you choose West, then you have to choose pre- or post-Reformation. Pre-Reformation is easier since you really only have one choice (Catholicism) but there are some variations on that theme we can ignore for now. If you go down the Reformation or Protestant path, well you've got several geographical variations and their offshoots to choose from, including German (Lutheran), Swiss (Calvin), or English (Episcopalian or Anglican). But it gets even more complicated, since those offshoots had offshoots, and you can also choose Baptists, Quakers, Mennonites. There are also Jehovah's Witnesses, Anabaptists, the Mormons (fundamentalist or reformed). In fact, there are about 38,000 different denominations of Christianity, most of which do not recognize any of the others as valid, many of which have engaged in brutal warfare over the years in an attempt to annihilate the other. So choose wisely. I know those odds - 1 in 38,000 don't sound encouraging, but at least we need not consider the majority of the world that is non-Christian, such as all the different denominations and sects of Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Chinese traditional, African, American, Asian, and European indigenous religions, Sikhism, Juche, Spiritism, Baha'i, Jainism, Shinto, Cao Dai, Zoroastrianism, Tenrikyo, Neo-Paganism, Unitarian-Universalism (which can include any of the above), and Rastafarianism.

Oh, and by the way, you don't have to choose at all. Many don't and lead perfectly happy, balanced, ethical lives.

The sheer diversity of human faith, many of which claim to be the One True Faith, should give any thinking person pause. They can't all be right anymore than all children can be above average. And the assumption that any religion is the One True Faith, evidence of an omniscient, omnipotent god has to explain why the vast, vast majority of those created by god do not adhere to that religion. All healthy, sane people will recoil instinctively from burning flame, experience sexual arousal, hunger, and thirst. We are hard-wired to respond to universal, cross-culturally robust truths. We don't need a priest to tell us water will slake our thirst or an imam to tell us not to step off a high cliff. Those things that matter are deeply ingrained in our central nervous system and universally evoked with minimal or no cross-cultural variation. The capacity for religious truth is clearly NOT universal or cross-culturally robust. The burden of proof rests with those who argue that an all-knowing, merciful god created us mainly to worship and adore him why he did not make such an important issue (the most important according to religious fundamentalists) as obvious and idiot-proof as fear of heights or fire, or desire for sex or food. A candle here and now has the power to teach, instruct, and persuade. Our capacity to feel that pain and respond to it has tremendous survival value. It is beyond absurd to assume that something as important as choosing the one correct choice of the menu of choices above would be shaped by the prospect of a theoretical postmortem punishment that would be as useless as it is cruel and gratuitous.

Simply presenting this menu to children (most of whom are never told there are other choices, or if so, that they have any validity) undermines the whole premise of most religions: the presentation of a universal explanation for how the world was created, where we came from, why we're here, and where we are going.

But most religious classes are not informing as much as selling. The sheer number of choices people make would be Exhibit A in the case against anyone having a monopoly on holy truths. It strikes me as dishonest and manipulative to present these things to children as fact. I have witnessed a number of Sunday school classes and Bible camps and have yet to see one that honestly presents a historically or even logically consistent case for Christian belief.

This brings up another pet peeve - that most who thump the Bible most forcefully have not actually read it (and if they did, they would probably stop believing it, much less thumping it), but that is not my main gripe. We cannot all be historians, amateur or professional, and reading both the accepted sacred texts of Mediterranean Monotheism and historical works about how they were written, edited, translated, and in some cases purged, takes a tremendous amount of work. For people with day jobs who just want to pass a little tradition on to their kids, it seems like a tall order.

But I think we can start with some humility. We can use the words "I don't know" more, and admit that 99% of religious affiliation is geography. If we really believe god will punish us forever and ever for what we believe, then we are saying that god is essentially punishing us for where we born, a geographical fact over which we have no control. It is possible we live in such a random universe, but if so we might as well enjoy our lives and stop groveling so much.

We can tell our children (they will find out anyway) that all religious traditions have done some shameful things, some are doing them now, and anyone who says he is infallible is lying. We can admit that we don't have all the answers and never will. No one does. We can say that we may all believe certain things to be true, but belief is a complicated thing with many inputs, including heritage, conscience, and personal life experience. Beliefs change with time, both societally and individually, and that's OK. In fact, in no area of our lives except religion is changing your mind to reflect new ideas and experiences seen as sinister. It's what adults do, even if it means that we have to admit we were wrong or mistaken. There is no shame in this. The fact that some people rationalize bad things does not mean that reason is always to be mistrusted anymore than the fact that some people justify bad things for religious reasons does not mean that faith is always to be mistrusted.

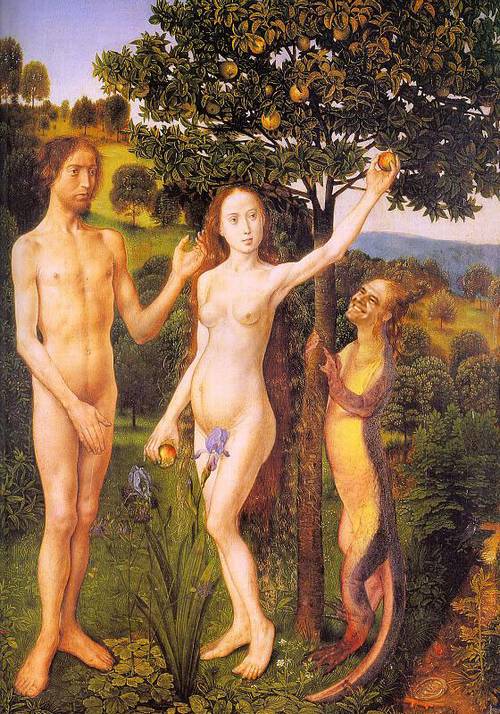

However, given a choice between the two, since there is so much disagreement about articles of faith, especially metaphysical ones, and since we must still use reason to determine which of the many articles of faith apply in a given situation, let's make sure our reasoning skills are fully honed and never completely abandoned or disparaged. The ancient Greeks believed, perhaps naively, that to know virtue was to do virtue, and that virtue and balance would lead inevitably to happiness. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, despite the legendary scholarship each tradition has spawned directly or indirectly, have at their heart a conflictual, sometimes overtly hostile relationship to knowledge. (What was the name of the tree whose forbidden fruit Adam and Eve munched on - the tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil?)

Doubt is part of the human condition. As Graham Greene said, to doubt is to be alive. It is what spurs us to be curious and to grow. Certainty breeds complacency and hypocrisy. Those who are certain about anything, whether in philosophy or physics, probably don't understand their field very well. Reality does not lend itself to simple explanations, although our mind finds such explanations comforting.

No religious or philosophical belief system has a monopoly on truth. This does not mean that all things are OK because they are not. All religious belief systems, at their core, believe in some form of the Golden Rule. Don't hurt. Don't kill. Don't lie, cheat, or steal. As Rabbi Hillel the Elder once put it when asked to explain the Torah to a skeptic while standing on one foot, "Do not do unto others as you would not have them do unto you. That is the whole of the Torah: go and learn it."

The world is much older and our place it in much smaller than those who wrote the books we call the Bible could possibly imagine. The fact that Biblical authors were so far off in their estimates of the age of the Earth (many millions of orders of magnitude), and so confused about the order that things must have been created (there could be no light before the light-generating objects such as the sun were created, for example, and the sun is one of many stars, so could not have been created first) indicates that the Bible cannot be taken literally.

My hats off the scribes of our time able to fit the most eloquent of retorts onto the smallest of t-shirts.

This does not mean of course that the Bible, however imperfectly it was written down, does not reflect in some way the words or thoughts of god, or that there is a god at all, but it does mean that it must be judged as one of many possible sources to wisdom and goodness. The fact that it sets itself up as infallible then stumbles in the first few verses does not inspire confidence.

If we are to read the Bible as poetry, fine, but the Bible itself commands us not to. This is the ultimate Catch-22: to take the Bible with all of its glaring inconsistencies and scientific inaccuracies evident to a reasonably educated middle schooler (but imperceptible to an agrarian, semi-literate, pre-scientific Mediterranean target audience) seriously, we must ignore large chunks of it including its commands not to ignore a single word of it!

Why not just start from scratch instead of twisting ourselves into a logical and ethical pretzel, trying to make ourselves fit a belief system that may have been appropriate for a world that believed women were inferior, slavery was inevitable, and the earth was only 7,000 years old, but clearly has long outlived its service as any kind of Life Owner's Manual.

The fact that its tone is often exclusivist, authoritarian, and dismissive of any other belief systems, enumerating villages and ethnic groups for destruction who have long since disappeared anyway, makes me wonder why we should accept such a transparently human document (or more accurately collection of documents, some of which are quite poetical and lyrical) as a moral anchor. When people such as Glenn Beck or Sarah Palin say they want to use this book as the basis of our country, I can only hope that they have not read it (if they have, I fear for our country).

If Beck is right, Jesus was just a progressive activist.

There are many stories in the Bible that are useful. We should be kind to the widow and the orphan and the outcast. We should share with the poor and give clothes and shelter to the homeless. All of these messages are found throughout the Bible.

But there are many messages that are downright harmful, clearly a product of a much more brutal and superstitious time. Extensive references condoning and supporting slavery, cruelty toward children, or subjugation of women come to mind. And what possible ethical lesson is there in a man murdering his son or his daughter (or being willing to in the first instance) simply because he heard a voice telling him to? If we are reading these stories to our children for some kind of moral instruction, don't they have a right to know if we would kill them if we got it in our heads that that is what god wanted us to do? And if so, shouldn't the next call be to child protective services or the police?

"You've got to be kidding me... NOW you tell me... It was just a TEST? ... YOU explain that to my son then."

No comments:

Post a Comment