This is from our August, 2009, trip to Normandy, but it is worth re-posting.

You advise me to forget.

Forgetting either happens, or it does not. Those who bear the wounds are still alive.

We do not want the graves to blend into nothingness,

The warning cry of the crosses carried away by the wind,

The burden of pain washed away by the rain.

We want that not the heroes but the sons be mourned,

Want the resounding words to be

packed away forever, not just for a time,

Want to avoid forgetting,

Lest forgetting be necessary again,

To appease future terror and pain.

If we did otherwise we would have to mourn for the unborn,

To whom we would be indebted,

Who would have to pay for our mistakes.

I please with the dead to stay with us,

To help prevent us from ever doing wrong again.

- Erich Kästner, 1899-1974

Wenn

die Menschen nur wissen würden, wie schwer es ist, verwundet zu sein,

zu sterben - alle wären mild und zahm, würden sich nicht in Parteien

spalten, keine Meuten aufeinander hetzen und nicht töten. Alle, wenn

sie gesund sind, wissen sie es nicht. Wenn sie verwundet sind, glaubt

ihnen keiner. Wenn sie tot sind, können sie nicht mehr reden.

- Mihajlo Lalic

[My

translation: If people only knew, how hard it is to be wounded, to die

- everyone would be mild and peaceful, would not splinter into parties,

would not incite mobs to attack one another and would not kill.

Everyone, when they are healthy, don't know this. If they are wounded,

no one believes them. If they are dead, they can no longer speak.]

Die in den Gräben ruhen,

warten aut uns, auf uns alle.

Sie waren Menschen wie wir.

Aber wenn wir in der Stille

an der Kreuzen stehen,

vernehmen wir ihre gefaßt

geworden Stimmen: Sorgt Ihr,

die Ihr noch im Leben steht,

daß Frieden bleibe, Frieden

zwischen den Menschen, Frieden

zwischen den Völkern.

- Prof. Theodor Heuss

Kriegsgräben mahnen zum Frieden.

[War graves are an admonition for peace.]

German Cemetery (La Cambe)

To be honest,

I was hesitant to visit the German cemetery.

We

had driven past one night; it was very eerie, ghostly. I walked

through a narrow door archway and stepped into a dark field before I

realized I was literally standing on a grave. Unlike the bleached,

white, almost triumphant crosses of the American cemetery, the German

gave markers were almost flush with the ground that mounded slightly

where each body lay.

The next day, we went back to visit by daylight.

Der betende Soldat (the Praying Soldier).

It

was actually a far more powerful experience than the American cemetery,

which at some level tried too hard to make sense of such horrendous

losses.

Denied

of the opportunity to create their own coherent narrative, or at least

one that included nationalistic references granted to the victors, the

Germans chose a more enduring and universal message, a monument to the

murderous madness of modern war. Simplistic explanations involving

freedom and nobility let the victors skip over the larger universal

questions such as why should anyone ever trust his government with

something as important as his life? or why did the fathers and

grandfathers of The Greatest Generation fail so badly, making their

sacrifice necessary in the first place? or was a frontal assault on

firmly entrenched positions the best that Eisenhower could come up with?

German POWs being guarded by an American.

Military cemeteries in Norway hold 177,000 fallen soldiers, American, British, Canadian, German, French, and Polish.

Most died between June 6 and August 20, 1944.

Most were less than 20 years old.

There are 18 British war cemeteries in Normandy alone.

In 1954, the Franco German War Graves Agreement was signed leading to

the Re-Internment Commission working to recover the bodies of German

victims from makeshift cemeteries and graves scattered in the fields.

The American Graves Registration Service buried both American and German

soldiers. German POWs were often assigned this task.

In 1958, young people from all over the world came to La Cambe and cleared the tree stumps and built an embankment at the periphery of the cemetery.

In 1961, over 1,000 family members traveled from Germany to France on a

specially-commissioned train and attended dedication ceremonies at La

Cambe.

21,222 German dead are buried in this cemetery that opened in 1958.

The American cemetery also did not open until 1957 - there was much

exhumation and re-burying of remains to consolidate a patchwork quilt of

cemeteries created in haste by the living whose main priority at the

time was probably not to join their fallen comrades.

After 1991, it was possible to visit areas previously blocked by the

Soviets or Warsaw Pact authorities for access by the German War Graves

Commission. They frequently stumbled on cemeteries that had been

raided and pillaged especially in the East.

Over 500,000 German remains have been recovered in Eastern Europe since 1991. The losses in the East were staggering:

3 million German soldiers died in former Eastern Block countries during WW II.

Unfortunately, as a species, we have learned little. As the museum reminded us,

40 million people have died in wars since 1945.

The individual names read the names from some of the tombstones hint at the individual stories the statistics numb us to:

GREN. Rich. Stollenwerk

* 16.4.26 - 9.8.44

STRM. Siegfried Nagel

* 19.3.25 - 23.8.44

+ EIN DEUTSCHER SOLDAT +

The

personal messages left by family members were quite touching. This one

read: "After over 50 years, it fills me with great sadness, that you

had to give your life for us. My father was buried under the rubble

(1943) in Stalingrad. One cannot and may not forget you!" [My

translation.]

"The loss of a loved one can never be forgotten. Where the dead rest is important. But it's not of ultimate importance. These men are dead and how much firmer should be our commitment to make the world a better place to live in. War is hell on earth. The dead bear silent witness to this."

- Joseph J. Shomon

"Fühle mit allem Leid der Welt, aber richte Deine Kräfte nicht dorthin, wo du machtlos bist, sondern zum Nächsten, dem

Du helfen, den Du lieben und erfreuen kannst."

- Hermann Hesse

"Gott hat das letzte Wort." [God has the last word.]

La guerre est une maladie. Comme le typhus.

-Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Over 14,000 French civilians in

the provinces of Manche Calvados and Orne died, mostly from air raids

and combat. (Excess mortality from nutritional and medical causes is no

doubt several times this number if other wars are any guide.)

Hundreds died in Gestapo camps, not all resistance fighters.

Walked outside to the headstones sunken and shared (often with an

anonymous "ein deutscher Soldat") with clusters of 5 somber tombstones

interspersed at regular intervals. Because the headstones are flat and

dark they give a much more somber impact but also understate by

appearance and number the sheer number of German dead buried here

alone. The arresting symmetry of the American tombstones catches your

breath until you realize most of the dead there were not from D Day (an

impression falsely given in some films and by a number of poloiticians).

At any rate, the German cemetery, although clearly much less lavishly

funded and less attended (it didn't even merit a mention in our Michelin

guidebook) was a vastly more powerful and honest testimony to the

random brutal savagery of war. There is no nonsense about freedom or

crusades here. The dead, few of whom chose their fight or their cause

anymore than they choose their parents or the geographical accidents of

their birth, were as much victims of the madness, whether combatants or

not. Because their leaders could not work things out, they sent their

children to kill each other and millions of teenagers perished.

As in the other museums and cemeteries, there were stories of individuals caught up in the carnage. Like Edmund Baton,

a pupil at the secondary school in Lauterbach in the Saar. He was

evacuated to ensure his safety. However, he took off with a classmate

toward home. He had to hide near Stuttgart to avoid getting involved in

heavy fighting going on there. At one point, Edmund convinced an

American soldier to take them along the Rhine as far as Strasbourg.

There they wanted to take a train home but were arrested on the way to the train station by French police then transported across France to Poitiers where they were held in an internment camp. He died of starvation on July 14, 1945. He was 14 years old. Edmund is buried in the German War Cemetery.

Think about that. The war was over, for all intents and purposes. He

was a noncombatant, a child, who just wanted to go home. He was not

arrested by the Gestapo or the NKVD but by French police who at that

time were under Allied control. He was sent to an Allied camp, where he

starved to death 2.5 months after Hitler committed suicide.

The concept of 'nationality' began to lose its meaning.

There were no clear boundaries at the front. All of them bled together

and formed just one line, a line which was constantly in motion.

The

American airmen were not about to distinguish between their victims far

below on the ground. Nor did we discriminate whilst we are caring for

the soldiers, all of whom suffered equally from the pains of thirst,

starvation and fatigue. In effect, a sort of comradeship was born of the

mutual experience, of the anguish that all of them shared. They found

unity in death. For ever. Our family mourned for them all, our guests

for one turbulent, embattled night of war.

I have never been able to forget them, and I do not wish to. Their memory is a sort of legacy which they left with me; the only thing of definite importance is being human, everything else is merely incidental. Each time I notice someone who overestimates or over emphasizes the importance of their nationality, of the color of their passport, regardless of which one, I am forced to remember these men.

"In most accounts of the battle [for Normandy] the suffering of the French civilians is forgotten. In the Département of Manche, Calvados, and Orne, over 14,000 men, women, and children died a cruel and violent death.

They were the victims of Allied and German bullets, bombs, shells,

mines and grenades. They died in their homes, buried in rubble and

debris, slain and suffocated. They died of exhaustion, of wounds and diseases which could have been easily healed in times of peace. Hundreds were murdered in the prisons and cellars of the German Gestapo, not all of whom had been active in the resistance."

- museum caption, emphasis added

I

was haunted for months by the image of my purse while students, their

bodies crushed between the concrete of two collapsed stories. Their

bodies could only be identified by their uniform numbers and their name

tags.

- Nurse Colette Vanier, 1944 training nursing students in Caen

To make sense of war, to explain it after the fact as something

necessary, good, or even noble seems obscene somehow, like explaining to

your children that it might be occasionally necessary to sacrifice one

or two of them for "freedom." It seems therefore logical that so many

of those glorifying the sacrifices of war never experienced it

themselves, like Ronald Reagan, whose flowery description of the bravery

of the Rangers scaling the cliffs of Pointe-Hoc to take out and hold

the batteries raining down death on the invading troops below, although

deserved in this case, are told by a man who, like fellow actor John

Wayne, felt his highest priority was not serving in combat but avoiding

it to make Westerns (or in Wayne's case, movies glorifying the very

slaughter he was avoiding).

The German cemetery reflected the views of Germans I had met who all

had parents or grandparents who suffered terribly from war and really

seemed to internalize the evil of it.

I don't know if the French got that lesson; the American take on war

seems to be simply not to lose one (advise easier given than followed).

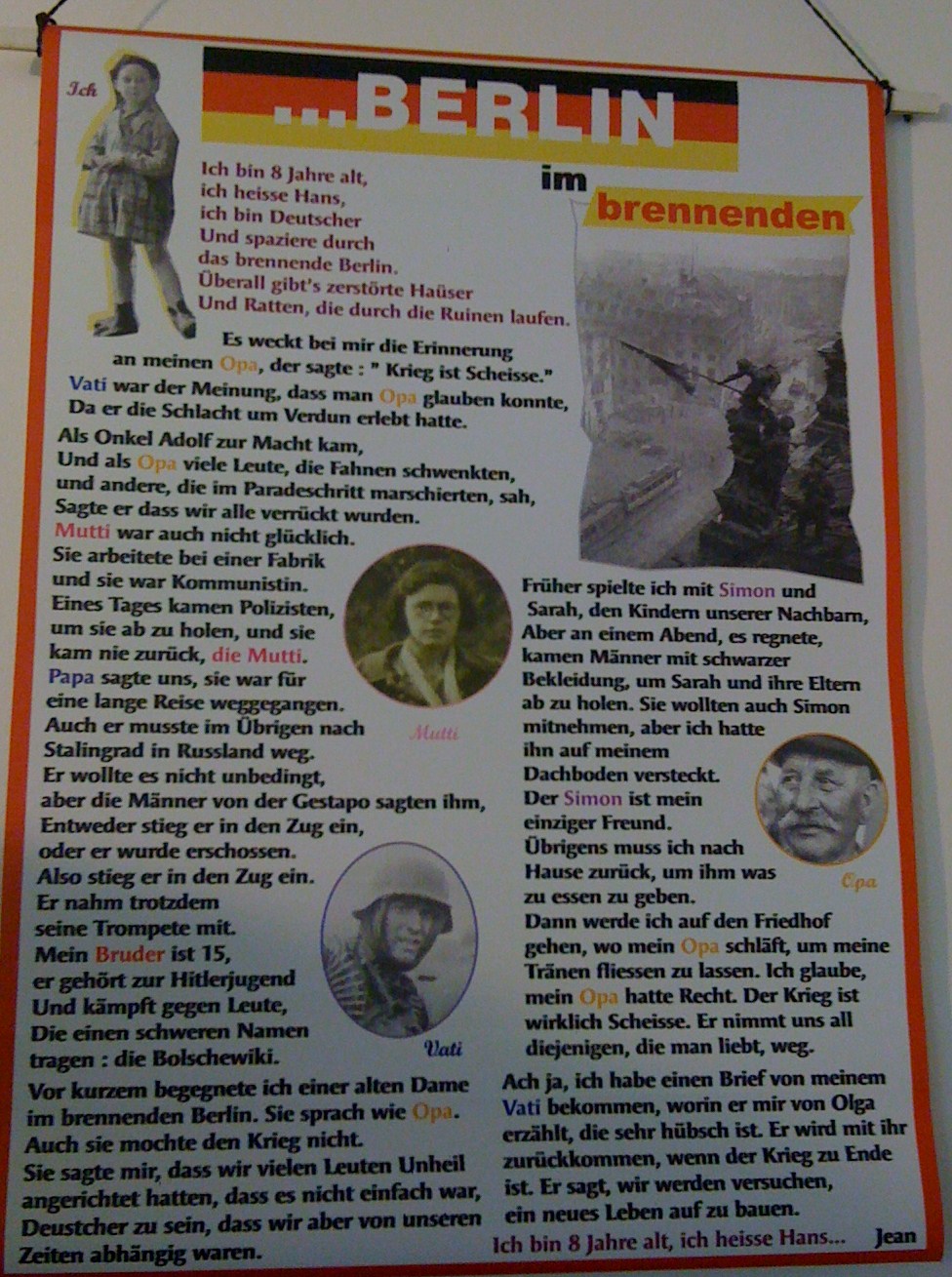

This

poster began with "I am Hans, I am 8 years old, I am German. I am

walking through the streets of a burning Berlin... and ends with "I got a

letter from my dad, in which he tells me about Olga, who is very

pretty. He will come back with her, when the war is over. He says, we

will try to build a new life. I am 8 years old. My name is Hans."

Die Wunden tragen, sind noch am Leben. [Those who are wounded are still alive.]

- Günter Eich

Der Friede ist das Meisterwerk der Vernunft. [Peace is the masterpiece of reason.]

- Immanuel Kant

Glaubt nicht, Ihr hättet

Millionen Feinde. Euer einziger

Feind heißt - Krieg!

- Erich Kästner, 1899-1974 [Don't believe you have millions of enemies; your only enemy is called War!]

Before a war breaks out, it has already begun long ago in the hearts of the people.

- Leo Tolstoy

If we accept that life is worth living and that man has a right to live then we must find an alternative to war.

- Martin Luther King

Memorial trees purchased by the survivors of the fallen. "In memory of my father, Lieutenant Erich K hne, gefallen October 1, 1944, in Modena."

May the eternal rest of so many victims be a warning and reminder to

this and future generations that these terrible events must never be

repeated.

- Pope Paul VI, 1897-1978